Labeling equipment for safety, continuity of operation

by Thomas F Armistead, Consulting Editor

We had a retirement party for old Joe last week. When he started at the plant, the smell of fresh paint was still in the air. That was 26 years ago. Joe absolutely knew the main-steam, feedwater, and condensate systems—every valve, every pipe, every piece of equipment. He ate, drank, slept, and lived it. We’re going to miss Joe. No one knows those systems the way he did.

If this sounds like the situation at your plant, there’s good news and bad news for you. The good news is that you have succeeded in retaining a knowledgeable, caring staff that keeps your plant running without a lot of fuss. The bad news is that when anyone retires, moves to another employer, or dies, that employee’s unique knowledge of your plant leaves with him or her. Yes, you can replace the employee, and eventually the replacement may come to know the plant as well as Joe did, but until he or she does, you’re flying on a wing and a prayer—hoping that the employee’s learning curve with the plant doesn’t end in a mishap.

If you have a guy like Joe at your plant, and he hasn’t yet retired, count your blessings. But if your plant is like many, your workforce may have a number of highly skilled nomads, just watching for a better opportunity with higher pay at another plant. Even with Joe on your staff, your luck can’t hold forever. During the recent economic downturn, a lot of people postponed retirement until their IRAs can recover some value. As they do, watch your exits.

“Through the recession, people have stepped back from retirement plans,” said Anita Decker, chief operating officer at Bonneville Power Administration. As the economy improves, she expects a lot of retirements—“a big bubble” of retirement demand has built up. Joe—and the other baby boomers on your staff—may just be waiting for the right time.

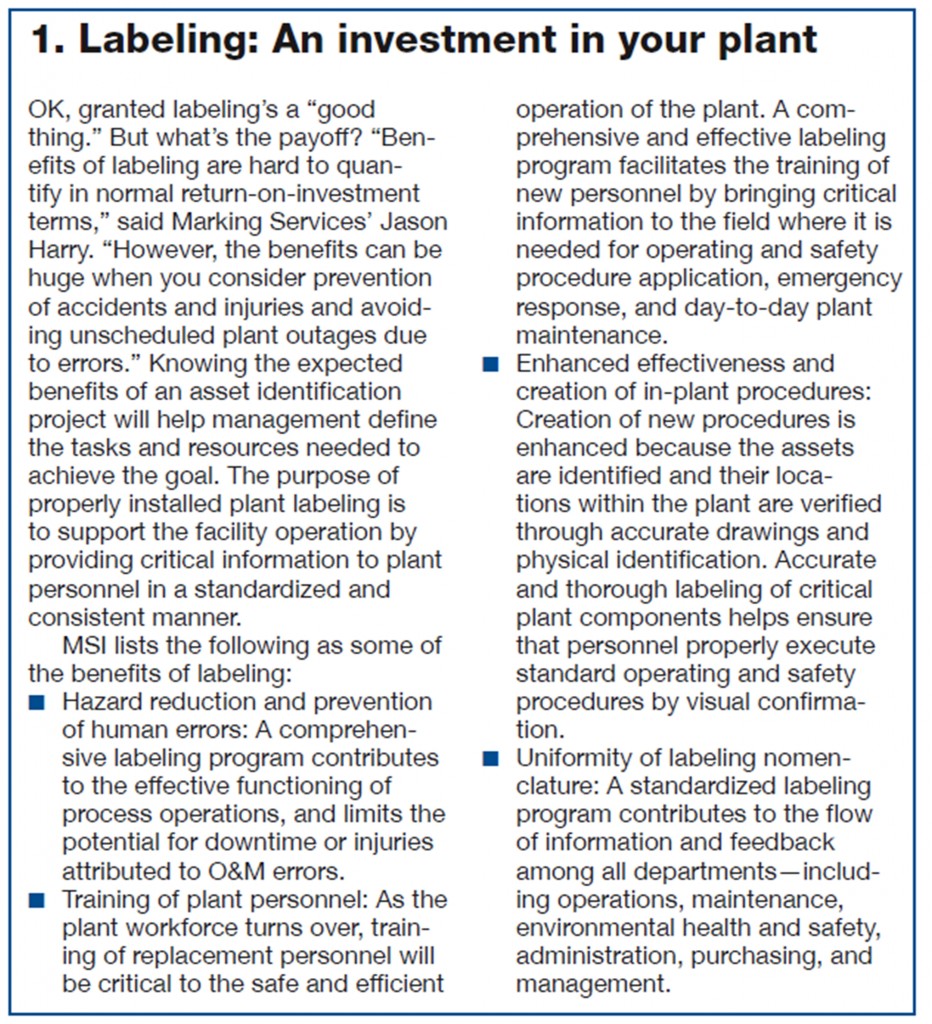

A good asset-identification or plant-labeling program won’t keep Joe on staff, but it can go a long way toward keeping his plant knowledge in-house and available to your staff. That knowledge could be the key to reducing the duration of an unplanned forced outage—or something much worse—in your plant.

Labeling program approaches

Many plant managers may see asset identification as a good way to train new employees and keep operators occupied during slow times while improving equipment labeling and line tracing, and they will launch the program mainly for those reasons. Gulf Power Co’s 970-MW, four-unit James F Crist Generating Plant, Pensacola, Fla, had no labeling system when it started adding small tags made in-house around 1997, said Jay Weston, Plant Crist’s asset manager.

“Using plant personnel, we didn’t make much progress,” he said. Later, the addition of air-pollution-control equipment created an opportunity. “With construction of the scrubber and SCR, we had the money and drawings to label at the end of each project,” Weston said. “Plant loved it, and now we are labeling another project with plans to start moving to existing plant equipment.”

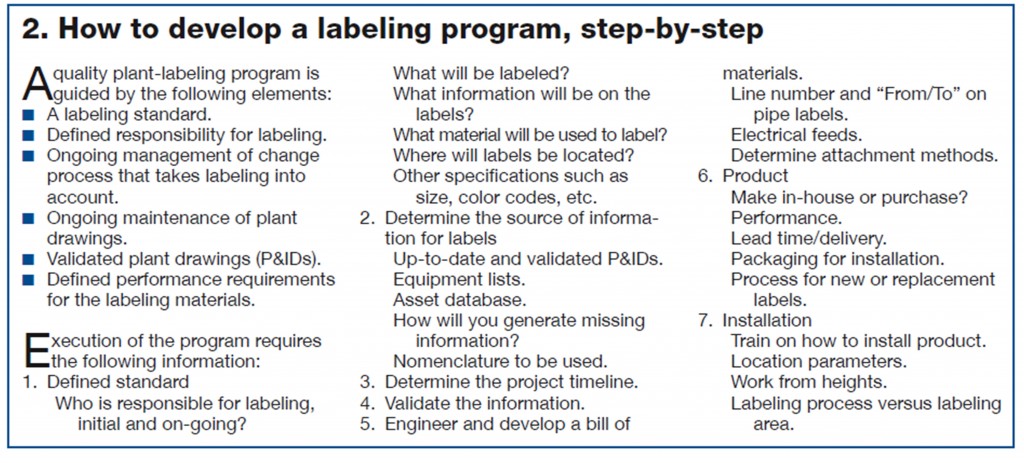

To Weston, labeling is more than a good idea; it’s good business (Sidebar 1). “Safety is one of the primary drivers to me,” he said. “It shortens time in the field locating and identifying equipment. Tagging insures accuracy. Also, we use tag identification for writing work orders and to give the person working on the equipment verification of what is isolated [Fig 1].” And not everyone working in the plant is familiar with the facilities. With labels on equipment, piping, and valves, plant management can give directions to contractors with confidence that the labels will help orient them.

Weston no longer does labeling work with plant staff, though. In 2009, he contracted with a company that specializes in creating and installing asset-identification systems, Marking Services Inc (MSI), Milwaukee. “We wanted someone who could furnish the labels and actually install them. That was part of our problem trying to install labels and tags with plant personnel: we couldn’t keep dedicated employees long enough to make any real progress,” he said.

Plant Crist’s difficulty is not unusual, said MSI’s Jason Harry. “Probably not very many [labeling projects] ever reach the level of completeness the plant intended. This is why MSI is in business,” he said. “The success of labeling programs begins and ends with how much value the management places on it. If management values labeling, they will support it financially. If not, you get operators writing on pipes with Magic Markers [Fig 2].” Some drawbacks to doing the work in-house, he said, include use of improper materials, labels lacking necessary information, and poor label placement (Fig 3). In addition, as Weston found, the job may never get done, or it may be done on premium time—nights and weekends.

In-house labeling has worked for nonutility generator Tenaska Inc, though. At the 270-MW Tenaska Ferndale Cogeneration Station, Ferndale, Wash, two GE Frame 7EA gas turbines with supplementary-fired heat recovery steam generators and an extraction/condensing steam turbine provide hydro-firming power to Puget Sound Energy.

The plant went commercial in 1994 with only the labeling required by regulations, said Plant Manager Tim Miller. The “above-and-beyond” labeling was done by plant staff using a vinyl label maker. There is no plant standard for labels. The labeling is governed by a company philosophy of best practices, which do produce results: The plant is an OSHA STAR work site, and has not had a lost-time incident since it began operation, Miller said.

Tenaska is aware of the value of good labeling. “We consider it essential for prudent operation, and it helps support all our major metrics—safety, efficiency, and reliability for our customer,” Miller said. Good labeling is important for safety because it ensures proper identification of systems, including whether systems are out of service and can be safely worked on, he added.

No respect

Comprehensive plant labeling is rare, in the experience of Charles Henley, chief piping engineer for powerplant engineer and constructor Black & Veatch, Overland Park, Mo. “Less than half of the powerplants get labeled,” he said. “If the client doesn’t specifically require something, we don’t do it.” That’s a common practice in industry, where labeling is “an afterthought,” he said, largely dependent on the type of client. An investor-owned utility company is probably more likely than an independent power producer to label its plants. Labeling also is “more regional than it is anything else,” he said, citing a plant in Alberta, Canada, where the owner wanted ASME 13.1 labels on everything. “They were very particular.”

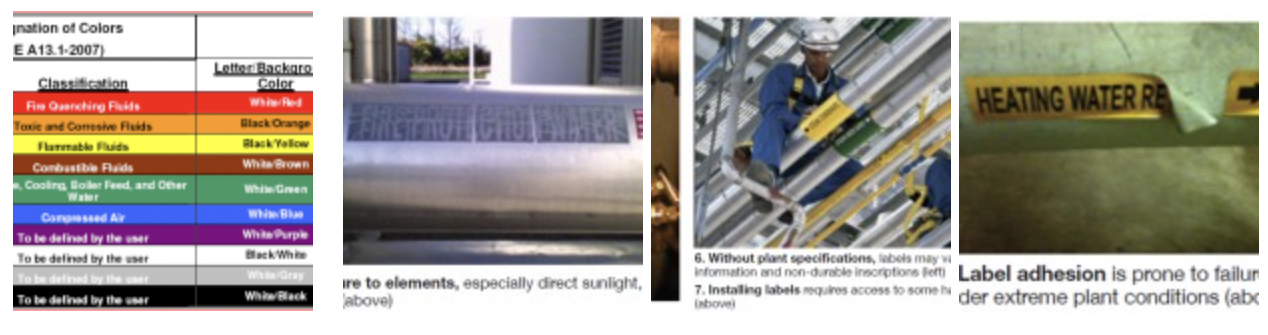

Labeling gets little respect from professional standards committees. ASME 13.1 (Fig 4) is the required standard for pipe labeling, but no sources cited any other national standards for powerplant labeling, only a handful of state standards. “There’s not really a requirement to put identification on piping systems,” Henley said. “We do it based on what our customer’s requirements are.” ANSI V 535.1 is a safety color code, but it’s not required, as ASME 13.1 is.

Henley guessed that only 10% to 20% of owners require labeling in their plants for piping systems that are not flammable, hazardous, or combustible, but the majority of the owners want tags or some other type of labeling on valves, equipment, and anything else an operator has to operate.

“Every plant has some kind of labeling but the thoroughness varies greatly,” said MSI’s Harry. “Older plants tend to be labeled with materials that were state-of-the-art at the time—stencils, brass, stickers, and engraved plastic. These materials don’t hold up well over time, especially if they are exposed to the elements (Fig 5). It is common to have a wide variety of labeling materials in the plant (Fig 6). This happens because no labeling specification is established for the plant.”

When developing specifications for your plant’s labeling system, consider inclusion of barcodes on all equipment labels. Scanning barcodes on rounds is one way to verify all equipment that needs to be check is actually checked. Further, barcodes enable O&M personnel to link directly to information needed to operate and maintain a given component while in the field.

Sources generally reported that they would expect the engineering-procurement-construction (EPC) contractor to do the labeling, but it normally happens only if the owner requires it. If an owner puts labeling in a contract, Black & Veatch will do it or subcontract it to an insulation or painting contractor, either of which can easily do it while the scaffolding is in place for their work, Henley said (Fig 7). The problem with that approach is that, without a plant standard, labels furnished by different contractors will lack uniformity, hampering communication, said Harry.

From all accounts, it appears that Marking Services is the only contractor that specializes in both furnishing and installing asset identification, and Henley did sub the Alberta plant’s labeling to MSI. But labeling is not high on an EPC’s priority list; it will be picked up later if at all, Henley said. In his opinion, labeling is best done by the owner’s staff because they know the plant. “If people aren’t familiar with an activity, stuff gets mismarked,” he said.

Sold on labeling

New Harquahala Generating Station (NHGS) is a 1092-MW plant with three Siemens 501G turbines in 1 x 1 combined-cycle configurations. An investors’ group, MACH Gen, Athens, NY, purchased NHGS at 60% completion and finished its construction in 2004. The plant is operated by NAES Corp, Issaquah, Wash.

Generating stations typically label equipment, piping, tooling, etc, as a means to improve safety through proper system identification. In addition, labeling enhances the training of station personnel, and plant reliability is improved by reducing misinterpretations of system components and associated piping.

“There was no equipment or tooling labeling in the plant when we started work, so we started down the path to do it in-house with our own team because we knew lack of labeling would be a systemic blind spot for us,” said Dean Motl, NHGS plant manager. “We ended up deciding this effort would be a very difficult, arduous process.” Ensuring standardization, identifying the locations for labels, making the labels, and making station staff available for the work were forecast to be too time-consuming to be overcome while attending to normal operations and maintenance duties. “Fortunately, we realized that we could not effectively complete the work in-house.”

“There was no equipment or tooling labeling in the plant when we started work, so we started down the path to do it in-house with our own team because we knew lack of labeling would be a systemic blind spot for us,” said Dean Motl, NHGS plant manager. “We ended up deciding this effort would be a very difficult, arduous process.” Ensuring standardization, identifying the locations for labels, making the labels, and making station staff available for the work were forecast to be too time-consuming to be overcome while attending to normal operations and maintenance duties. “Fortunately, we realized that we could not effectively complete the work in-house.”

Local environmental conditions further complicated the task, as New Harquahala is located in a region of high heat and intense sunshine. The station needed labels made from materials resistant to chemicals and heat (Fig 8). Searching for possible solutions at a tradeshow, Motl found MSI and was impressed with the company’s product. MSI, which specializes in UL/CSA labels, warning/caution labels, nameplates, graphic overlays, membrane switches, bar code labels, and insulators, was ultimately awarded a services contract for the station’s labeling needs.

MSI took the plant’s piping and instrumentation diagrams and line drawings, and proposed a list of labels, Motl said. MSI and plant staff met to confirm the accuracy and completeness of the list and to maximize efficiency of effort. When confirmation was complete, MSI printed out marking stickers and walked down the plant to place the stickers. That was followed by walk-downs to verify accuracy and approve placement. Only at that point were labels made. Label hanging took about a month, and did not interfere with plant operations or production.

The consistent labeling improved the plant’s aesthetics and provided a sense of pride and professionalism for the station staff, and when visited by regulatory and governing agency personnel, Motl said. Whenever the plant updates its equipment, he added, it sends a list of changes to MSI and new labels are prepared to match the existing scheme “to ensure consistency with the plant’s best-in-class initiatives and alignment with NHGS ownership and NAES core values.”

Brian Paetzold was in the Navy and is now the assistant director for three NV Energy powerplants near Las Vegas: Chuck Lenzie, Harry Allen, and Silverhawk Generating Stations. “The Navy is the de facto standard for labeling,” he said, and he likes to apply his Navy training to labeling his plants.

Brian Paetzold was in the Navy and is now the assistant director for three NV Energy powerplants near Las Vegas: Chuck Lenzie, Harry Allen, and Silverhawk Generating Stations. “The Navy is the de facto standard for labeling,” he said, and he likes to apply his Navy training to labeling his plants.

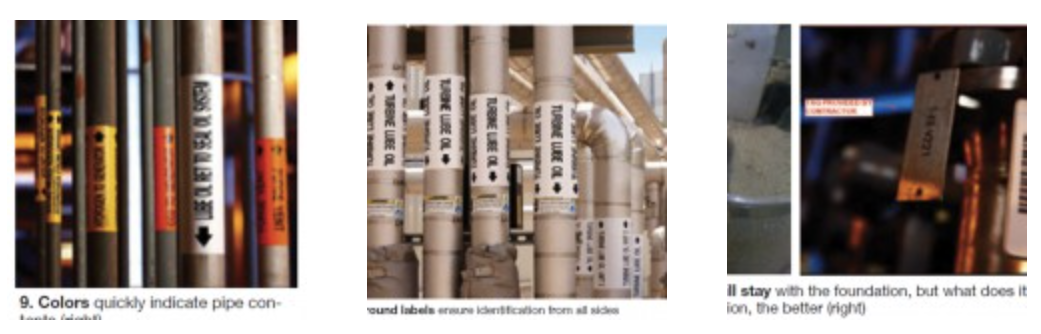

A good labeling system uses colors to identify components that have similar functions, he said (Fig 9). It should use a suitable font, visible at a distance, and arrows showing process flow so operators know at a glance what the flow is. The labels and signs should be visible from multiple angles (Fig 10). Labels on a piece of equipment should be affixed to the foundation so they will remain in place if the original equipment is replaced (Fig 11).

Black & Veatch’s Henley also likes to see spring-formed labels wrapped around a pipe because they won’t peel off when heated, as an adhesive label can. Letter size should be proportional to the pipe size, with high contrast between the colors for the lettering and the background. Flow arrows also are important. On equipment labels, he likes to see the system name, the purpose of the valve, and the valve tag ID number, with stainless steel wire holding the label on the valve or equipment (Fig 12).

NV Energy bought the partially completed 1102-MW, 4 x 2 combined-cycle Chuck Lenzie Generating Station in 2004 and completed it in 2006. Harry Allen Generating Station last year completed the addition of a 484-MW CC system to what had been a pair of 72-MW combustion turbines operating in simple cycle. Paetzold contracted with MSI to provide labels for both plants. NV Energy doesn’t have a standard for labeling, so he relied on MSI’s system. “Lenzie has been identified as a strong leader in labeling and a model for the rest of the fleet,” he said.

Operators at these plants are showing other sites in NV Energy’s system how their labeling works. To illustrate the benefits of good labeling, Paetzold points to Lenzie’s air-cooled condensers. A technician inside a cell can think he’s in a different cell from the one where he actually is, and thus may do maintenance on the wrong cell. Signage clearly visible from inside the cell in two directions tells the technician the cell’s identity.

“One of the important things about labeling is the safety aspect of it,” Paetzold said. Technicians know exactly which piece of equipment they are working on, and quickly see if they are in the wrong place. He has heard of instances when labels caused people to halt work when they realized they were in the wrong location.

Lenzie’s labels have been in place for about four years and have faded in the direct sunlight, so the plant is relabeling now. NV Energy doesn’t have a protocol for label maintenance, but it does a health and safety audit every two years, and can include a label walk-down to identify labels needing replacement or updating.

Joe, of course, never needed the labels anyway; he knew the plant. But Joe is fly-fishing in Patagonia now, and he’s not coming back. Who has taken his place? And what does his replacement know about your plant’s systems? CCJ