Cogen plant controls replacement: ‘non-proprietary’ is key

Solutions for upgrading and/or replacing control systems at generating facilities powered by gas turbines continue to proliferate, getting more and more creative all the time. For Veresen Inc’s Ripon Cogeneration facility (operated by NAES Corp), a 50-MW steam-injected LM5000 cogeneration plant in California’s San Joaquin Valley, the watch word for the replacement was “non-proprietary,” according to Brett Weber, O&M manager. Weber defines what this means for his 25-yr-old plant: “We want to be able to buy [control] cards from a vendor down the street.”

Ripon evaluated many vendor offerings but in the end, focused on local parts availability and local support to further reduce the total cost of ownership.

Plenty of other considerations guided the decision to replace, especially obsolescence and the pain of struggling with a legacy system—standalone controls for subsystems, antiquated reporting and documentation, recurring failures with the historian, data loss, and corresponding time lost retrieving data. On top of everything, vendor support had dwindled to next to nothing.

“Whether we had nuisance or critical trips, our staff couldn’t get into the program to determine what caused the trip or why the unit wouldn’t start—something like transmitter x was out of range—so we were always troubleshooting multiple problems,” recounts Weber. Because the system was essentially copper wire to the control room from I/O cards communicating through Ethernet in the field, every trip or malfunction required lengthy field work. “Following a turbine trip, we’d have to search through pages and pages of DCS alarm documentation,” notes Weber.

Obsolescence wasn’t the only issue, though. Ripon supplies distilled water to a neighboring process facility and sells power into CAISO (California Independent System Operator). Previously, the general operating mode was to start and stop every day. Now, says Weber, under a new contract with CAISO, the plant only runs when dispatched. Fast starts and flexible ramping are paramount.

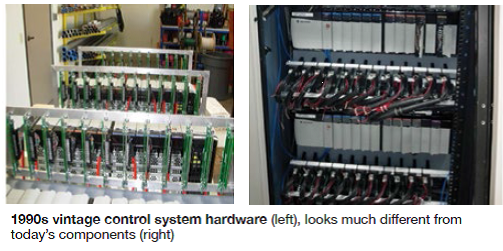

Replacing the proprietary WDPF control system, described by Weber as “generation 1” and featuring 5-7-in. floppy discs and multiple computer workstations, with a Rockwell Automation PlantPAx™ DCS system (figures) satisfied the objectives. The new DCS solution, however, was supplied through Maverick Technologies LLC, Columbia, Ill, which not only had experienced WDPF experts on hand, but a front-end evaluation process Maverick calls DCSNext.

According to Rockwell, PlantPAx offers advantages in scalability, flexibility, and advanced functionality. Examples of the last include embedded time synchronization, rack-based historian, sequence-of-events capture, integrated condition monitoring, virtualization, and intelligent motor control.

Now, states Weber, “we have so much more control over every aspect of plant operations.” All of the “islands of automation,” including emissions monitoring, gas-turbine controls, chiller-plant controls, and reverse-osmosis (RO) system, are integrated into a common set of screens. It takes only one guy to start up the plant, where it took two operators previously, one in the control room and one at the equipment, because 50-70% of the “controls stuff” was out in the field. “About the only function that isn’t automated is HRSG blowdown,” says Weber. Nuisance trips have been reduced by 90%.

Now, states Weber, “we have so much more control over every aspect of plant operations.” All of the “islands of automation,” including emissions monitoring, gas-turbine controls, chiller-plant controls, and reverse-osmosis (RO) system, are integrated into a common set of screens. It takes only one guy to start up the plant, where it took two operators previously, one in the control room and one at the equipment, because 50-70% of the “controls stuff” was out in the field. “About the only function that isn’t automated is HRSG blowdown,” says Weber. Nuisance trips have been reduced by 90%.

“When we make a change to the physical components, we just snap new cards in or remove old ones.” Weber illustrates this ease: “We added ammonia detectors in the chiller area to detect leaks, and shut down the system in the event of one. It took 30 minutes to make the changes in the control system. The only hard part was putting in the new automated valves,” he notes. Unlike with the old system, Ripon makes these control system changes with the facility operating.

Better heat rate and added flexibility are two big-ticket improvements. The plant’s environmental permit requires that full load, or compliance-level emissions, be achieved within one hour. States Weber: “Using the old system, we could do it in 57-58 minutes, on the ragged edge of what is acceptable. Now we are there in 40 minutes.” The new ramp rates allow them to make a “few extra bucks” in the ISO, and while Weber says it’s difficult to properly monitor heat rate because of gaps between the actual and design machine heat-rate curves, “we know we’re burning less natural gas.”

A smaller gain is that the new control system reduces the heat load through the control equipment by 60%, with a corresponding reduction in air conditioning requirements. “The AC in the control room used to run 24/7. Now the operators are freezing because it’s so oversized for the current duty,” jokes Weber.

Weber underscores three important lessons learned from the project for the many others who will be undoubtedly embarking on control-system retrofits:

1. You can always use more historian data points, but they are expensive. Whatever number of points you think you need in the beginning, double it, and embed that into the initial capex. Ripon’s PlantPAx includes 750 process points and a historian servicing 1000 points.

2. Training: Don’t expect the site guys to sit down when the replacement is complete and start running the plant. Operators need to become familiar with the system before it is installed. Brett notes there was much he would have done differently here.

3. Upfront planning is essential—you can’t afford extra downtime. It is a huge task to prepare everything so the installation and the changeover go smoothly. Monitoring of the factory acceptance tests (FAT) is crucial. For Ripon, the FAT of the physical I/O went “really well.”

For Ripon, the changeover was accomplished inside of two weeks, including five days for the point-to-point testing in the field and three days for controls integration. CCJ