As an integral part of its operational-excellence core principle, NV Energy recognizes that human errors or gaps in its processes can directly, sometimes significantly, impact safety as well as operational performance, reliability, and assets. Reducing and eliminating these errors and shortcomings is the essence of its ongoing Human Performance Improvement (HPI) initiative.

The goal is to transform operational groups into learning organizations where discovery, investigation, and problem-solving become collaborative at every level. Widespread involvement and a culture of trust are necessary to truly expose the organizational weaknesses that lead to human errors. This requires firm leadership alignment from top to bottom so that when mistakes happen they are used as learning opportunities.

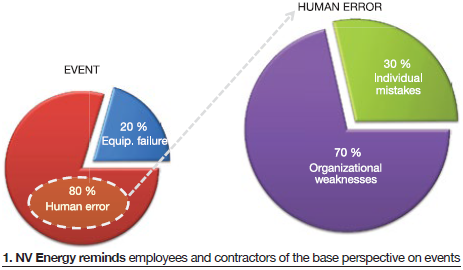

Perspective. The first distinction is to separate human activity from equipment operation and stress. Equipment malfunction or failure reportedly accounts for only 20% of a plant’s reliability loss, human involvement (human error) the remainder (Fig 1).

But the latter goes far beyond errors by individuals. The human-factor category includes collective weaknesses, norms and traditions, management styles and systems, almost anything non-equipment. In fact, most of the human element (seven times out of 10) can be classified as organizational weaknesses—including such strong influences as ownership or management changes.

In that context, a concentration on HPI makes a lot of company-wide sense, and should not be taken personally. It only makes the team better.

Many organizations have launched initiatives to address these factors and occurrences. NV Energy’s HPI program is robust and underpinned by five fundamental platforms. They are:

- 1. Event tracking.

- 2. Reporting.

- 3. Root-cause analysis.

- 4. Communications.

- 5. Proactive error-prevention tools.

When something unexpected (think unwanted) happens, the immediate task is to trace its origin—thoroughly and objectively.

Event tracking and reporting

“Any human action which directly or indirectly causes a significant event triggers the tracking process within the HPI system,” says Steve Page, project director for NV Energy’s generation organization. The tracking system calls for clear identification of the immediate direct cause or causes. To help, examples within a web-based system are listed for both behaviors and substandard and at-risk conditions.

Significant events fall into one of the three following categories:

- 1. Safety. Any OSHA recordable incident.

- 2. Environmental. Notice of violation or spill reportable to an outside agency.

- 3. Production. A unit forced outage or capacity de-rate greater than 20%.

The examples are further defined as either behaviors or conditions. Acts/practices/behaviors include such things as failure to warn, operating without authority, deviation from standard procedure/practice, etc. Substandard/at-risk conditions include inadequate warning system, defective protective devices (or none), substandard tools or equipment, etc.

Each incident is reviewed by local leaders along with corporate leadership and support personnel. The events are mined for learnings to be shared throughout the company.

Root-cause analysis

Root causes are more defined, more varied, and require specific identification of underlying details to draw accurate conclusions. Take, for example, physical capability, inadequate training, poor procedures, bad planning, and poor risk perception.

A clearly defined distinction between error and violation is often significant. An error is “an unintended deviation from expected behavior due to a multitude of reasons.” A violation is “an intentional deviation from an expectation or expected behavior that the individual is knowledgeable and proficient in performing.”

According to Page, “It is NV Energy’s observation that incidents of willful violation are not common. Almost every mistake has a root in an organizational weakness. Therefore, candid and open discussions best occur in a threat-free environment. This is key. Without trust and employee engagement, a human-performance initiative will not yield much benefit.”

Proactive tools.

NV Energy has carefully selected and defined specific tools to reduce both errors and violations, and to ensure that the HPI program is effective and long-lasting. Specifically, NV Energy uses:

- Self-checking.

- Peer checking.

- Place keeping.

- Three-part communication.

- Phonetic alphabet.

- Two-minute drill.

- Stop!

Self-checking is an error-prevention technique specifically designed to boost the performer’s attention to important or critical details before executing a task. The basic format is stop, think, act, and review (STAR).

Take, for example, the lock-out/tag-out (LOTO) process:

Step 1 (Stop) requires the person to pause before engaging in the process, ensure they are fully engrossed in the process, focus attention and minimize distractions, and, in the face of any uncertainty, stop and review the procedure.

Step 2 (Think) asks these questions: Are you on the correct equipment (and at the right unit), does the tag terminology match the equipment, are all the energy sources and work-scope details identified and understood, and do you understand your responsibilities to NV Energy and/or to the contractor?

Step 3 (Act) means first to physically approach the equipment and confirm the tag information, then focus on the tasks of hanging the tags and locks. Next, the person must walk down the entire LOTO boundary, then communicate and correct any deviations from plant protocol.

Step 4 (Review) means to verify isolation points and tags for accuracy, ensure verification is witnessed by Operations and the first LOTO holder, verify that all signatures are recorded on the proper forms, and confirm that any deviations are reviewed, corrected, and communicated to everyone involved.

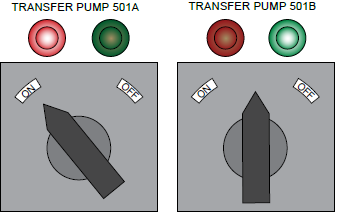

Sidebar illustrates the process involving a transfer-pump switch.

Illustrating self- and peer-checking

A transfer-pump switch is used here to illustrate both self- and peer-checking. The task is to operate a switch; the “act” is to move the pistol grip to the “on” position. First step is to pause and consider what needs to be done. Next, verify the correct equipment and anticipate what could go wrong.

NV Energy offers specifics:

TOUCH the pistol grip and leave your finger on it until you get to the “act” step. Then do the following:

- READ the document OUT LOUD that directs manipulation of the component.

- READ the component label OUT LOUD, checking to make sure it agrees with the document.

- VERIFY the device is in the anticipated position.

- Then, without losing eye contact and without removing your hand,

- Move the pistol grip for Transfer pump 501A to the “on” position and anticipate contingencies.

The last step is to review and confirm that the expected results did occur. Did the red light come on and the green light go out? Did the pump start? Any other indication: amps? pressure? sound?

NV Energy requires a self-check when:

- Operating a component or switch.

- Feeling rushed or distracted.

- A task is interrupted.

- A task is critical.

- Significant risk is involved.

And always (with peer-check) on LOTO and confined space.

Peer-checking. To complete a critical task with even higher assurance of first-time success, NV Energy uses a peer-checking system (basically STAR with a co-worker). Communication allows verbal checking and confirmation of all steps. When the component label is read aloud, the co-worker verbally confirms. During actions, the co-worker watches closely and confirms. During review, the co-worker verifies and offers any advice for the future.

Peer-checking at NV Energy is required when:

- A task is performed for the first time. First time performing a task.

- Potential exists for significant consequences.

- The person would feel more comfortable.

- The supervisor requires it.

- Past experience dictates it.

- Always on LOTO and confined space.

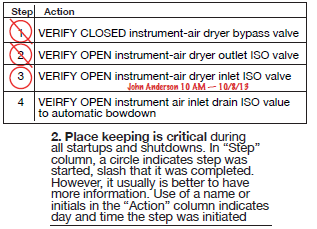

Place keeping. For written procedures, NV Energy also stresses place-keeping techniques such as circling the written step number in a procedure, both verbalizing and performing the step, then placing a slash through the number before moving to the next step (Fig 2). This also can be used to acknowledge steps that might not be applicable. Signatures, initials, dates, and times also could be required. Place keeping is required for all written procedures, and during all unit startups and shutdowns.

Three-part communication is a technique that ensures messages are understood correctly before any action is taken. This is used every time a directive is given. First, the sender identifies the receiver by name and provides the initial message. Then, the receiver acknowledges receipt by either paraphrasing or repeating back the directive verbatim. Paraphrasing helps both parties verify full understanding. Third, the sender acknowledges that the response was correct. Actions can then take place.

Keep in mind that the third part (sender acknowledgement) is often the weakest link in this chain.

Some basic rules are important, such as avoiding the use of slang or regional words, and giving multiple instructions. At NV Energy, this technique is required when:

- Communicating operational information or directing operational tasks.

- Communicators are in high-noise areas.

- Processes or procedures are critical.

- There is a risk of miscommunication.

- There is use of radios, telephones, or other communications devices.

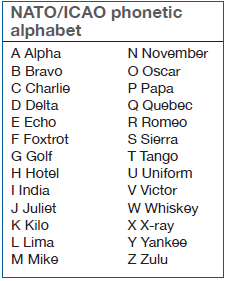

The phonetic alphabet is a common tool to ensure communications are clear, concise, and accurate. This eliminates confusion when dealing with letters that sound alike (b,t,p,v,d), when an acronym could be confused with another acronym, or when dealing with components with similar names. The NATO/ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization) phonetic alphabet is the most common (table). An important point: This is used during verbal, not written, communication. Written letters are visually distinct.

The phonetic alphabet is a common tool to ensure communications are clear, concise, and accurate. This eliminates confusion when dealing with letters that sound alike (b,t,p,v,d), when an acronym could be confused with another acronym, or when dealing with components with similar names. The NATO/ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization) phonetic alphabet is the most common (table). An important point: This is used during verbal, not written, communication. Written letters are visually distinct.

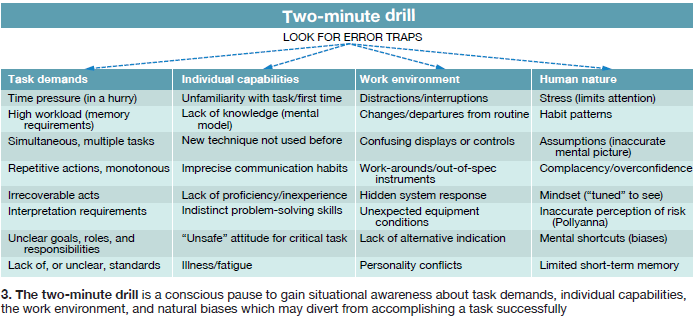

The two-minute drill simply means taking the time to evaluate a job site for safety and error concerns. Typical questions to consider are permission requirements, hazards in the area (above, below, and ambient), and protective equipment requirements—among others. NV Energy emphasizes use of the two-minute drill on first entry at a location, as well as after an interruption of any type or length.

Procedure and work-package writers often do not have direct access to witness all site conditions, and are not generally present on the day the work is implemented. Thus, the two-minute drill gains critical importance. Work conditions can vary from those in the procedures, and even from the daily pre-job briefing.

And if a person is experiencing a gut feel about something, this is the time to raise it. “Never think that a job is easy, simple, or routine,” states Page. This is the time to look for what NV Energy identifies as common error traps—such as distractions, inaccurate assumptions, time pressure, unfamiliarity, interruptions, or personal stress (Fig 3).

Stop is perhaps the most critical tool, allowing pause in task performance to verify that all key details of the task have been addressed and understood. The pause in action can be initiated by anyone. The cornerstone rule is to fail conservatively, meaning if the task or environment is not playing out as intended, it is imperative to stop and re-stabilize the situation. “Never proceed in the face of uncertainty,” says Page. CCJ