Sharing ideas, and solutions to problems encountered in operating and maintaining powerplants, is why users groups were formed by owner/operators. Talen Energy is a big supporter of these self-help all-volunteer organizations, its personnel actively participating in several—including the Combined Cycle and 501G Users Groups.

An idea sure to generate discussion at upcoming meetings comes from Colleen Dolan and Regina Chan and their colleagues at Talen’s Athens Generating Plant, operated by NAES Corp. The three-unit, 1080-MW, 501G-powered facility is located 30 miles south of Albany, NY, a stone’s throw from the Hudson River.

Plant facilities include two storm-water basins designed to safely capture and release natural and facility discharge into federally protected wetlands. The man-made ponds are monitored by the New York State Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Permit Program.

Since commissioning in 2004, the ponds, located in opposite corners of the site and designated the northeast and southeast ponds, have become overrun with vegetation, mainly cattails and sumacs. Such vegetation is often found at power-generation facilities, especially those surrounded by woods and wetlands.

Storm-water ponds become inefficient when overcome with vegetation. And when pond berms attract vegetation (other than grass), root systems can undermine the berms causing leaks. At Athens, the cattails also attracted muskrats, which began making holes in the berms. Plus, obstructed visibility of the site’s perimeter was a security concern. Thus, vegetation control became a critical part of facility maintenance.

Proper pond maintenance is critical for both operation and environmental conservation. Generally, storm water refers to runoff that does not soak into the ground, and can travel into waterways. In the case of Athens, that eventually leads to the Hudson River. Storm-water runoff collects pollutants and debris as it travels, enabling concentrations of materials that can cause damage to lakes, rivers, wetlands, and other water bodies. Thus it can have negative impacts on animal and plant life, plus sources of potable water, and other things as well.

Because containment and controlled discharge are part of Athens’ state permit program, vegetation must be controlled.

Cattails, aquatic perennial plants, overwhelmed the Athens ponds. Three species of sumacs (Staghorn, Smooth and Poison) also appeared in and around the ponds. These shrubs and small trees produce flowers with dense pinnacles and fruit. Sumacs can reach a height of 30 ft.

The northeast pond is designed to collect and release water from natural sources and from the Athens facility. When vegetation became an apparent problem, the pond’s discharge pipe was closed for long periods in an attempt to raise the water level where cattail growth would not be induced. The area also was brush-hogged. These two actions significantly reduced the need for vegetation removal and maintenance. But the pond berm and surrounding area soon became an alternative growth area, and uncontrolled sprouting became a new concern. Extensive mowing is the current viable solution.

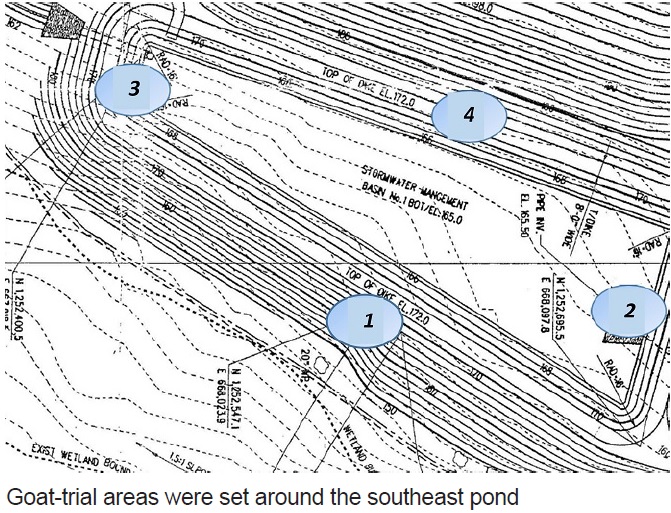

The southeast pond (map) also is designed to carry, collect, and release, but the facility has not yet been required to open its discharge pipe. Water collected in this pond is from rain and occasional release from transformer containments. Therefore, the level normally is low, providing an ideal environment for vegetation growth within the pond. Both cattails and sumac have flourished and have invaded the berms and surrounding areas. Brush hogging, extensive mowing and manual labor have not decreased the problems. Some cleanup activities actually have increased the progression of these plants.

Actions and alternatives. Biocides and herbicides were never an option for vegetation control. Alternatives were discussed with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, concluding that mechanical removal would be the most appropriate. But New Athens had attempted mechanical means since 2011 and these had proven neither economic nor efficient. The vegetation would return.

Sometimes the best solutions are relatively simple and, in this case, local.

Athens personnel contacted a local farmer who raises goats. They are herbivores, naturally clearing land with their insatiable appetites, and capability to ingest a wide variety of plants. Their natural craving includes cattails and sumac. For the more tree-like sumac species, goats will eat the bark or use it to clean their horns, in addition to eating the leaves. This prevents new shoots from growing.

After surveying the southeast pond area, the farmer was willing to locate a small herd of 10 goats in a fenced area for eight weeks. He would visit daily to bring water, check animal health, and oversee progress. This became a trial run to determine whether or not the goats would be comfortable and willing to feed on the overgrowing vegetation. Goats were placed in four different areas of the pond throughout the eight weeks to test their appetites and adjustment to the environment. The results:

Area 1. The southern area of the southeast pond is a steep hill that meets the Conrail Railroad tracks east of the Athens facility. This zone is filled with sumac and had grown into a miniature forest. The view of the tracks (and security perimeter) was obscured by the dense canopy of leaves and thick branches. This area was chosen the first test because of its abundance of sumac.

Within 48 hours, the goats had made significant progress, eating away at the sumac leaves and cleaning their horns on the bark. Within 10 days, and view of the railway was significantly improved. Approximately half of the trees were stripped bare as the goats targeted the staghorn and smooth sumac. They also ate the grass, flowers, and weeds.

The goats concentrated on the steep hill. The untouched vegetation was either plants that they could not ingest, were too high to eat, were poison sumac, or were staghorn containing white flowers (young sumac getting ready to bloom).

Area 2. The goats were moved to the second zone after 10 days. This was the pond area containing cattails and surrounded by sumacs and other vegetation, and was the area of most concern to the facility (pond discharge pipe).

However, because of poor weather and standing water in the pond, the goats did not venture into the base but instead only grazed on the sides, eating the sumac trees. Their sensitivity to water overruled their preference for cattails, reducing their overall impact. They ate approximately 35% of the area, consuming leaves and breaking down barks, impeding future growth.

Area 3. After 14 days in Area 2, the goats were moved to a zone densely populated with shrubs and weeds on the hill and with staghorn and smooth sumac at the base. This was the smallest test area, bordering a larger natural habitat. Thick vegetation made it difficult to monitor progress. The goats cleaned approximately 25% of the vegetation, primarily on the hill. Rain accumulated on the ground floor where other sumac resided, and the goats were soon moved to the next area.

Area 4. The final test zone was the north region of the southeast pond. This area is also a hill that meets with an adjacent fuel oil tank. It is not filled with cattails but instead consists of tall sumacs, shrubs, bushes, and common weeds. The goats could graze and then rest under the tall trees during hot days.

Approximately 40% of the area was cleared by the feeding. Another 10% was eliminated through sun exposure as the goats stripped the bark and ate the roots. Their preference for sumac reduced any significant impact on other shrubs; they would break the shrub leaves and pull on branches but would not consume them. The farmer became concerned for their nutrition and they only remained for one week.

Results. This trial seemed to benefit the facility, the goats, and the farmer. For the plant, approximately 40% of the overall vegetation in the test pond area was cleared. It was environmentally sound; the vegetation was reduced and nutrients were restored back to the ground. It was also economical, providing a sensible program with positive results. For the farmer, the goats were well fed and grew quickly.

Roadblocks were identifiable. Water in Areas 2 and 3 limited the goat herd’s potential to clear away cattails. Dislike for young, tall staghorn sumac in Areas 1 and 4 limited overall clearing of sumac. But the trial provided first-hand experience and useful data for future trials and programs. Many roadblocks (water accumulation, for example) can be reduced with early planning.

Goat trials will resume in summer 2018 at other plant areas.